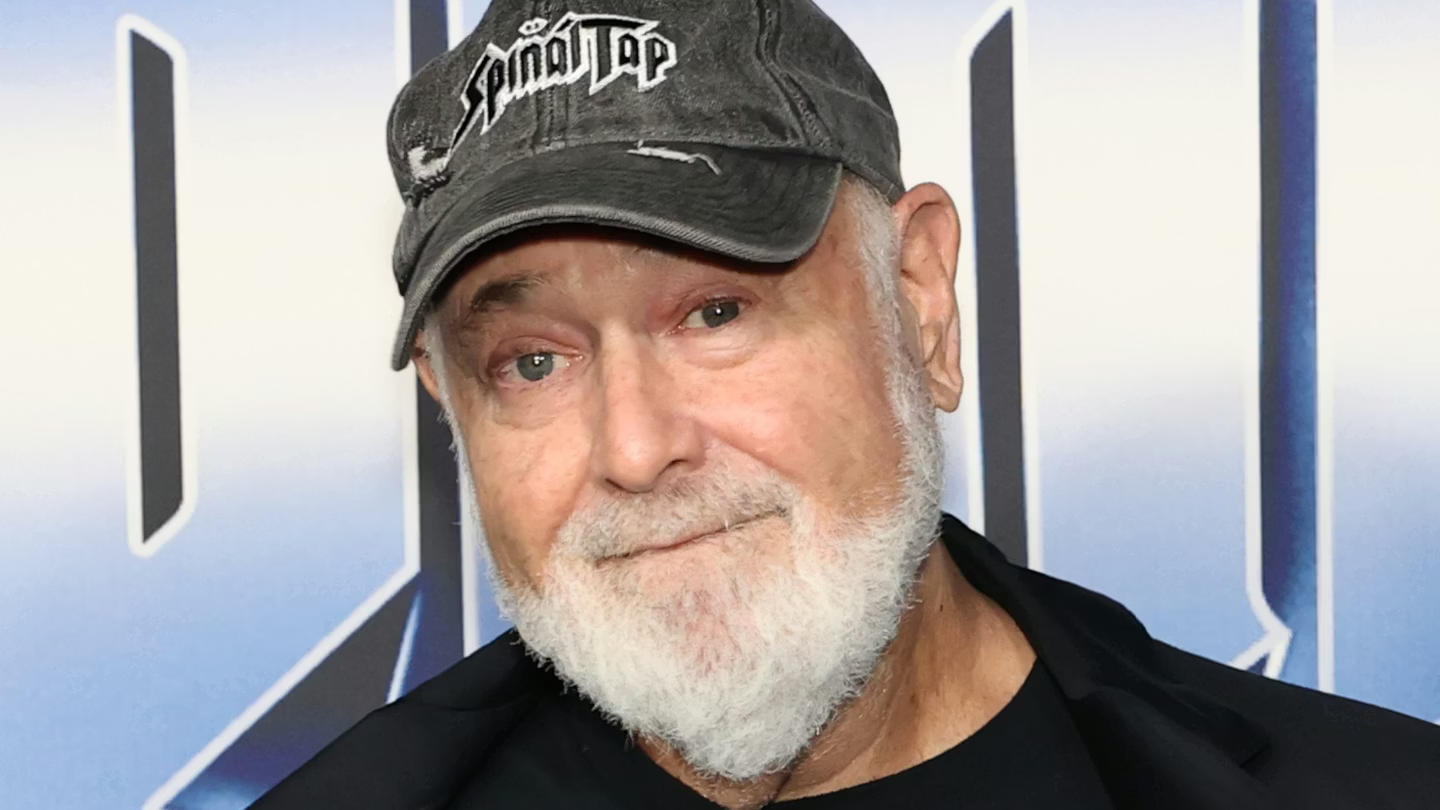

Rob Reiner: A life spent making the world laugh, feel, cringe, and cry

There are artists who chase a signature style, (your Spielberg’s and Kubrick’s for example), and then there are artists who chase an audience’s heartbeat, as if they were movie fans first and decided to direct the film you’re watching. Rob Reiner is one of these types of directors. He made comedies that became part of the quoted lexicon, dramas that made you feel like you got bruised watching it, and Hollywood crowd-pleasers that somehow still carried the weight of a point-of-view. In Hollywood, a town that rewards the boring and safe with repetition, Reiner’s had range. He made a mockumentary so sharp it rewired comedy, then pivoted and delivered a tour-de-force coming-of-age classic, a generation-spanning fairy-tale romance, a romantic comedy that still defines the genre, and a courtroom drama that has been quoted for decades.

And he did it all while staying loudly, stubbornly engaged with the real world outside the theater, putting his name and money behind causes he believed were urgent, from early childhood development to marriage equality.

From comedy family royalty to “Meathead”

Reiner was born in 1947 in the Bronx, the son of Carl Reiner and Estelle Reiner, and moved to Los Angeles as a kid. It is almost too perfect that someone raised around comedic craftsmanship would grow up to become both a performer and a builder of comedic worlds.

Reiner was born in 1947 in the Bronx, the son of Carl Reiner and Estelle Reiner, and moved to Los Angeles as a kid. It is almost too perfect that someone raised around comedic craftsmanship would grow up to become both a performer and a builder of comedic worlds.

Before he was a famous director, Reiner was an improv guy and a TV guy, writing for The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and popping up in TV roles, then landing the defining acting break of his early career: Michael “Meathead” Stivic on All in the Family. The nickname was a joke, but the character wasn’t. “Meathead” was the liberal counterpoint to the arch conservative father-in-law in one of TV’s most important domestic battlegrounds, and Reiner played him with a mix of conviction and exasperated humanity that made the clashes feel like real family arguments instead of sitcom exercises. It was a role earned him five Emmy nominations and two Emmy wins.

That performance matters because it tells you what Reiner valued even then: people. Not types. Not punchlines. People.

Reiner refused to be one “thing”

When Reiner moved into directing, he didn’t just transition. He hit the ground running.

His feature debut, This Is Spinal Tap (1984), did not merely parody rock culture. It invented a new comedic grammar. The “serious documentary tone applied to ridiculous subjects” has become so common now that it is easy to forget how novel that precision once was. Reiner worked alongside Christopher Guest, Harry Shearer, and Michael McKean, with much of the dialogue improvised, and Reiner himself playing the fictional documentarian Marty DiBergi. (The Library of Congress later added the film to the National Film Registry.)

Then he kicked it up a notch with films that are on most people’s must see lists. Over the next six years:

Stand by Me (1986) is a Stephen King adaptation that rejects horror in favor of memory. It is about boyhood, fear, bravery-as-performance, and the quiet trauma of growing up too fast. It’s a coming-of-age story that became a sentimental favorite and helped launch young stars like River Phoenix, Will Wheaton, Jerry O’Connell, and Corey Feldman.

The Princess Bride (1987) is a fairy tale that winks without sneering. It is romantic without being corny, funny without being disposable. (The Library of Congress also added it to the National Film Registry.)

Then came When Harry Met Sally… (1989), the romantic comedy that permanently raised the bar on what the genre could do with dialogue, timing, and honesty. Reiner had a gift for letting smart characters stay smart. He trusted conversation the way action directors trust stunts.

Then came When Harry Met Sally… (1989), the romantic comedy that permanently raised the bar on what the genre could do with dialogue, timing, and honesty. Reiner had a gift for letting smart characters stay smart. He trusted conversation the way action directors trust stunts.

And then Misery (1990), which proved he could do claustrophobic dread and psychological violence without losing storytelling control, earning an Academy Award win for Kathy Bates.

And then A Few Good Men (1992), which turned moral outrage into crowd-pleasing entertainment, the kind of movie that feels like it was built to play in packed rooms with people leaning forward together. And career performances by Tom Cruise, Jack Nicholson and Demi Moore and so many others.

That’s not just a hot streak. It’s a career thesis: Reiner believed the best mainstream storytelling could also be precise, character-driven, and emotionally adult.

Acting as a side dish, not the meal

Even after he became an A-list director, Reiner kept acting, often as a kind of punctuation mark in other people’s films. He’s Marty DiBergi in Spinal Tap, of course. And he shows up memorably as Jay, Sam’s friend in Sleepless in Seattle (1993), a role that People magazine explicitly highlights as part of his on-screen presence beyond directing. Later, he was hilarious as Jordan Belfort’s father in The Wolf of Wall Street, playing against Leonardo DiCaprio.

It’s fitting that he never seemed to act like someone “slumming it” when he acted. He brought the same thing he brought as a director: clarity, timing, and a sense that the character existed before the scene started.

Castle Rock and the larger footprint

Reiner’s legacy is not only the films he directed, but also the infrastructure he helped build. Multiple outlets note that he co-founded Castle Rock Entertainment, which became a significant force in film and television and is associated with major hits including Seinfeld and The Shawshank Redemption.

That matters because it speaks to how Reiner thought about storytelling as a sustained ecosystem, not just a single project. He wasn’t only making movies. He was helping shape what got made.

Activism that wasn’t just a hobby

Reiner’s politics were never a coy “I care, but don’t quote me.” He was publicly engaged for decades, and two lanes stand out as defining.

Early childhood development and health. He directed the TV documentary I Am Your Child(1997) and successfully advocated for California funding tied to a tobacco tax initiative. Coverage of his advocacy around California’s early childhood movement, including efforts connected to tobacco-tax funding, frames him as a public figure who used celebrity strategically, not performatively. (His tenure in that space also drew controversy at points, including a reported resignation as a state commission chairman in 2006 amid political scrutiny, underscoring that he was operating in real-world trenches, not just lending a name.)

Marriage equality. Reiner was closely tied to the legal and advocacy fight against California’s Proposition 8. The Hollywood Reporter notes he helped found the American Foundation for Equal Rights. AFER’s own archived materials reflect its role in challenging Prop 8 in court. Deadline’s reporting on his political impact also discusses his involvement in that effort.

You can agree or disagree with his politics, but it’s hard to argue with the consistency: he showed up, repeatedly, for issues he thought shaped people’s lives at the ground level.

A death that feels especially cruel

The report of Reiner’s death was a shock to all of us who love film. The cruelty is not just the violence, but the abrupt silencing of someone who spent a lifetime making work built to be shared. A voice was taken that left many of revisiting some films growing close to 40 years old and wondering if there will ever be another director with range as broad as his, or another human with a voice he lent so willingly to causes that he care about.

The report of Reiner’s death was a shock to all of us who love film. The cruelty is not just the violence, but the abrupt silencing of someone who spent a lifetime making work built to be shared. A voice was taken that left many of revisiting some films growing close to 40 years old and wondering if there will ever be another director with range as broad as his, or another human with a voice he lent so willingly to causes that he care about.

Reiner is survived by family, and he leaves behind a filmography that functions like a map of modern American mainstream cinema at its best: funny without being empty, dramatic without being pompous, and accessible without being cheap.

Viewing and understanding Reiner

If you want the cleanest summary of Rob Reiner’s career, it’s this: he was a maker of classics who never treated the audience like a target. He treated them like collaborators, as fellow movie goers. That is why his movies keep getting handed down. Parents show their kids The Princess Bride. Friends quote Spinal Tap like scripture. Couples argue about When Harry Met Sally… like it’s a relationship test. Film students still study the muscular simplicity of his storytelling choices.

A director can’t ask for much more than that. Not immortality. Just rewatchability. Just the next person hitting play.